Love In The Form Of Sacred Outrage

WeFreeStrings (ESP Disk')

The NYC Jazz Record, October 2022

“Romance… can bloom even here in white racist land; it can bloom as beautiful though flawed by our oppression, bloom bloom bloom, in the tradition of revolution, renaissance, Negritude, blackness…”

Amiri Baraka In the Tradition For Black Arthur Blythe

Melanie Dyer's latest incantation, Love in the Form of Sacred Outrage, performed by the historically named WeFreeStrings, is in the tradition of revolution and renaissance. The ESP disk draws inspiration from three black activists, Amiri Baraka quoted above, Civil rights activist Fannie Lou Hammer, and slain Black Panther Fred Hampton, on tracks one, two, and four composed by violist Dyer, pausing to bloom on the third track Pretty Flowers composed by Baba Andrew Lamb.

Read More

This offering opens with Baraka Suite, many years in the making, and consists of six movements, one of which takes the line Who? Who? Who? from the poem Somebody Blew Up America as its title. I wonder what Baraka might have penned about his suite. William Parker does an admirable job with his companion notes in evoking a space for the music that is both free, complex, political, and personal. Listening, I have to focus to make the connection between the militancy and the music, but as Sun Ra once said, “it's all in there.” It is just a question of making the commitment to focus as we go from bells to melody to atonal swing, worth holding on for the musical ride.

Melody Dyers' posted biography certainly shows the Avante-Garde and classical traditions from which her music has sprung, which are meshed with the traditions of revolution and resistance. From creating a salon in Harlem dedicated to hosting creative revolutionaries to exploring music compositions and performances, visual art, producing events, and supporting arts organizations, Melanie Dyer is a force to be reckoned with in the music.

Dyer formed the band in 2011. This incarnation consists of Dyer on viola, Charles Burnham and Gwen Laster on violin, Alexander Waterman on cello, Ken Filiano on bass, and Michael Wimberly on drums and percussion.

The opening 25-minute track brings us a cymbal and bells overlaid by the deeper sonorous register of the strings in a plaintive inquisitive melody. This, as the title Meditation on Earth implies, is meditative music, and the full band is involved in creating this reflective space, sometimes with aching beauty. The tempo is one of a dignified pace. The second movement In the Theater picks up the pace a little as the band swings into unidentified solos from each member of the string section. The aforementioned Who? Who? Who? challenges with an insistent rhythm on the viola while the next movement is more otherworldy and spaced out, including an extended drum solo. The suite closes with There Me Go, in which Dyer's viola sings a bittersweet lament.

Love in the Form of Sacred Outrage was written for the civil rights activist Fannie Lou Hamer. This four- minute title track features the strings without percussion and feels far more improvised than the suite. Pretty Flowers, also featuring strings, is the only track composed not by Dyer but by Andrew Lamb. The strings intertwine leisurely over the bass and soar together, creating sonic flowers for the ears.

The final track Propagating the Same Type of Madness, that uh... is dedicated to Black Panther and activist Fred Hampton, who was assassinated in 1969. The full band reunites for this closing track which is somber and dirge-like in its approach. This CD is a tone fest to be savored slowly over time.

For more information, visit espdisk.com. This group is at Soup & Sound Oct. 8th. See Calendar.

Read in The NYC Jazz Record

Carla Cook

Interview by Monique Ngozi Nri

The NYC Jazz Record, March 2022

Carla Cook has a unique vocal quality. She came to NYC to sing the way she wanted to over 30 years ago and received a Grammy nomination for her debut, It's All About Love, in 1999. Dem Bones , a tribute to the trombonists that she has worked with, was released in 2001 and Simply Natural followed in 2002. These recordings were lovingly produced by the MAXJAZZ label and received great acclaim. Cook has a repertoire that spans a broad range, from gospel and R&B to the Great American Songbook and Brazilian songs and rhythms. She has collaborated with many musicians while balancing a teaching career. We caught up on her musical background and the inspiring music she continues to make.

Read More

The New York City Jazz Record: Tell me a little bit about your start in the music.

Carla Cook: I did come up in Detroit and the music scene was very vibrant, not just the jazz scene but, of course, Motown and the funk scene and all of that. I did very little work there because I left Detroit at 18 to go to college in Boston. And I never returned. So I did not really work the scene so much in Detroit. A lot of musicians that I know I will work with when I came back over the summers or whatever, so I would get to know some of them that way. But I can’t claim that I cut my musical teeth in Detroit.

TNYCJR: But you did sing in church?

CC: Absolutely, I sang in church, I sang in choirs. I did the whole state honors choir. I played bass in the orchestra in high school. I played piano and took private piano lessons, so I have a mix of European classical training and I sang in the AME church, the Black Methodist Church.

TNYCJR: Did you find any conflict between your classical training and gospel and moving into jazz?

CC: I remember having the nerve to tell my European classical voice teacher that I wanted to sing jazz and he was so offended, but good voice training works no matter what genre you’re trying to approach. So, I just took that training and I’ve been able to apply it to other things. Nothing and no one ever told me that I couldn’t! We had a wonderful jazz radio station WJZZ in Detroit and they mixed it all up. There was a big band hour and blues hour. And because of that and the fact that I was surrounded by all these different kinds of music and participating in the honors choir here and then church there, I didn’t have boundaries, I didn’t attend an institution that told me that I should.

TNYCJR: I know you don’t like to be boxed in. I actually was just listening to “Hold to God’s Unchanging Hand” just before we started talking. What is the place of the sacred and the secular in your music?

CC: When I recorded “Hold On God’s Unchanging Hand” my mother had passed a few years before and that happened to be her favorite hymn and so I was recording that for her. I had no idea that it would take on the life that it did. I mean, a lot of radio stations, especially in the Midwest and South, that was kind of the only thing they would play. They weren’t really interested in the swing so much as in the gospel song, you know, but I sing that song relentlessly to this day. It’s one of the first that stayed in my repertoire the whole time. I’ve sung it in Kazakhstan and Israel. Where I sing it does not matter and I usually tell the audience that sometimes I’m not singing it necessarily for them but for me.

TNYCJR: Tell me more.

CC: I sing it as a reminder, the lyrics are a reminder. Not just the business but in day-to-day life I’m really trying to adhere to my personal spiritual belief. Hold on to God’s unchanging hand, especially now there’s so much going on. Yeah, pandemic aside, there’s still so much going on and so [these words] keep me focused, filled with gratitude at the end of the day.

TNYCJR: I was also reading somewhere that it’s important to you that the music is progressive. Is that accurate and, if so, what does that mean?

CC: I’m not sure what you mean by progressive. I always tell people that jazz, it seems like every ten years someone tries to proclaim jazz is dying or is dead. You know this music sells itself. That’s why it’s been around for so long. That’s why generations keep gravitating toward it because it’s still relevant. I think the problem is in educating very young people. Of course, commercial radio is no more and then we decided as a society that music wasn’t all that important for us in schools and we decided that sports were definitely important but the music wasn’t, so now we’re paying for it.

TNYCJR: I know that you’ve done a number of different things in education. You have your own educational project that you took around in the schools.

CC: Right, unfortunately, that was just before the economy sort of tanked and, quite frankly, only a few school systems have had the funds to pay for it, but the truth is, all kids need music education. They need music just like they need math and I say this often, nobody swings like third graders. There’s an elementary school in Long Island called the Washington Rose Elementary school. They had a fantastic principal and she just believed in this music and they had a handful of the best faculty and we went there every year. And the third graders they had, I have put songs back into my repertoire because of them, because I’m teaching it to them. A lot of this music is not necessarily geared toward children. That year, I don’t know if the theme was Ellington but for some reason, I brought in “In a Mellow Tone”, which I had known a hundred years ago. I taught it to this particular group of third graders. They had such a vibe to them. I’m listening to them just swing and I’m like why am I not doing this? And then this is what’s great: they sing it and they loved it. And because they all ate lunch together there’s one class singing it, three days later and the whole school knows the song.

TNYCJR: There is a big debate about people being trained in schools and not being trained on the road. Do you have any thinking about that?

CC: I taught at Temple University for 13 years in the undergrad program and for the last three years at Juilliard. The short answer is I totally believe in formal education. There is no debate for me. There is a place for sure, but it is not the only place. I went to Northeastern University and my undergraduate degree is in speech communication. I got a lot of my training just hanging out with musicians, but also I was able to ask Betty Carter a question. I go to the masters and ask them. That’s education. There are a lot of ways to come at this and I think formal education is a great way to do it but it is not the only way.

TNYCJR: It doesn’t seem to have been your quest to be recorded. I only see three albums and I also found this spoken word thing Inside Voices . Do you have any projects or anything under your own name forthcoming? I know you stayed with MAXJAZZ and then they were taken over by Mack Avenue.

CC: Yeah, Richard [McDonnell, MAXJAZZ founder] passed away some years ago. I have, I can’t say no desire. The thing is, the industry has completely changed. Since I recorded and I’m tech-averse and there’s so much about recording now that has nothing to do with making music... However, I have had two different projects in my head and I simply have not gone to the studio to pursue them... Right now I’m able to thank God I’m still able to have this great balance of working with other people on different projects, doing my own projects here in the United States and, every now and then, teaching. It’s all balanced out that it feels good right now.

TNYCJR: Talk about the Harlem Stage gig.

CC: This venue has been around for many years and it’s been a place where all these artists could go and especially uptown artists. I think I was there to see someone when I first came to Harlem, I mean when I first came to New York.

TNYCJR: Are you focusing on any particular music, or is it going to be a range?

CC: As always, it will be a range. But I am going to make an effort to do a tribute to some people that we’ve lost over just the last period of time.

TNYCJR: Do you know the personnel in the band?

CC: I’ve got, while he’s not new, just new-ish working with me, drummer Jarrett Walser. [Pianist] Bruce Barth is a jazz mainstay, known everywhere. He’s co-produced all of my CDs. And then the great Kenny Davis, one of jazz’s most sought-after bassists. We worked together for hundreds of years. And so it’s always exciting for me, especially when I have such a great group. It makes it really easy when you got musicians you feel like you’re really in good hands with and that makes you take on some musical risks and a lot of times that’s when the magic happens.

For more information, visit carlacook.com.

Recommended Listening:

- Craig Harris & The Nation of Imagination– Istanbul (Doublemoon, 1997)

- Carla Cook–It’s All About Love (MAXJAZZ, 1999)

- Carla Cook–Dem Bones (MAXJAZZ, 2001)

- Carla Cook–Simply Natural (MAXJAZZ, 2002)

- George Gee Big Band (featuring Carla Cook)– Setting The Pace (GJazz, 2004)

- Regina Carter–I’ll Be Seeing You: A Sentimental Journey (Verve, 2006)

Read in The NYC Jazz Record

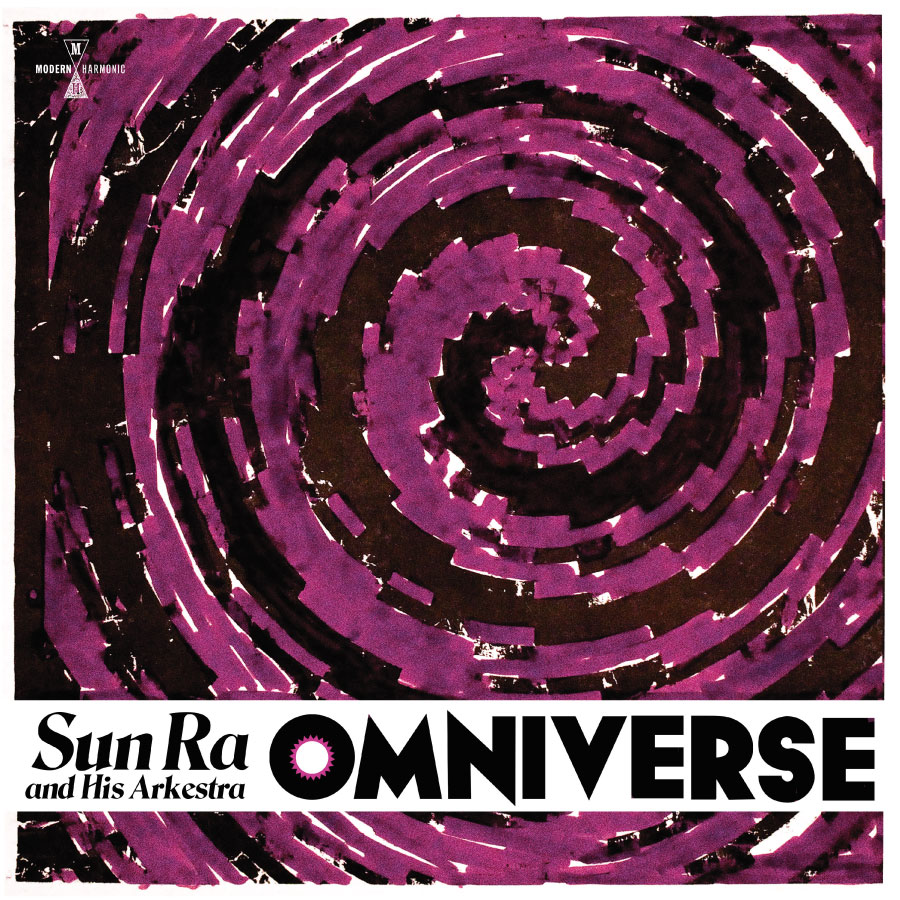

Omniverse

Sun Ra and His Arkestra (Modern Harmonic)

The NYC Jazz Record, January 2022

The opening chord from Sun Ra's piano introduces the pathway to a mellifluous John Gilmore on tenor saxophone in a ballad so lush it is barely Sun Ra except for the mysterious intervals and slight sonic dissonance so characteristic of his music. The subject of the opening piece, “The Place of Five Points”, is the place of Sun Ra's arrival on the planet: Birmingham, Alabama. The solo Gilmore takes hits both the high and low registers in a way that both calms and excites the brain. Bassist Hayes Burnett and drummer Samarai Celestial provide sporadic rhythm and otherwise highlight and accent the glittering keyboard display. “West End Side of Magic City”, also a name for Birmingham, swings with vibrant interplay between Sun Ra's eclectic chords and Gilmore in very much a call-and-response affair. John Szwed notes in his book Space is the Place that Sun Ra was ambivalent towards the Magic City, suggesting he saw the city also as a place of “fantasy, a city without evil, a city of possibilities and beauty.”

Read More

Greg Tate, the great writer/thinker of Black culture who left the planet on Dec. 7th, 2021, wrote of Ra: “The omnidirectional pursuit of musical, philosophical and poetic inspirations from historical, mythical and futuristic sources is a Ra staple.” It is a drag that as the Arkestra comes into its own with a first Grammy nomination that Tate is no longer here to comment on what this renaissance means for the future of the Afro-Futurism canon into which he placed the Arkestra, borne from what he describes as Sun Ra's “rallying, recombinant fusion of cosmic darkness and African Blacknuss.” That combination is present in full force on “Dark Lights in a White Forest”. We hear a full array of horns, from Michael Ray's muted trumpet to Gilmore's tenor flurries and intonations of Charles Davis' baritone. As the longest track at just under 11 minutes, it provides an opportunity for the players to stretch more than on the prior tracks. The last notes on muted horn eerily call out to space.

The title track to this 1979 session (originally on El Saturn) is also what Sun Ra often named his Arkestra and the impressive discography of Sun Ra's compiled by Hartmut Geerken (who died on Oct. 21st, 2021) and Chris Trent also bears the name. The definition is a universe that is spatiotemporally four-dimensional; perhaps that means a fourth dimension encapsulating all forces for transformation, a concept at the heart of Sun Ra's philosophy. The music is sublime and surprisingly gentle, the slow tempo, combined with mellow interweaving of piano and horns, having an almost hypnotic effect. “Visitant of the 9th Ultimate” also has a relatively slow tempo to start before swinging up to a brisker pace. This is the closest the recording comes to the omniscient, omnipotent, omnipresent heat of Sun Ra's larger ensembles.

According to the notes on the back of a beautifully packaged vinyl, replete with a heliocentric circle of purple on the cover, at least three of the compositions are not recorded elsewhere, so this offering serves as an important part of Sun Ra's oeuvre. Sun Ra stares out of a black and white photo also on the back cover, a glittery sun emblazoned on his chest. His eyes are unshielded by candy cane spiral sunglasses. He looks serious about his mission. Back to the AfroFuture!

For more information, visit Modern Harmonic.

Read in The NYC Jazz Record

Sun Beams of Shimmering Light

Wadada Leo Smith/Douglas Ewart/Mike Reed (Astral Spirits)

The NYC Jazz Record, December 2021

Sun Beams of Shimmering Light was created live at drummer Mike Reed’s Chicago music venue Constellation in 2015. The word is used advisedly as this is how one of its primary architects, trumpeter Wadada Leo Smith, describes himself. “I’m a creator,” he told this reviewer. “An artist makes art by creating through inspiration...without the artist’s inspiration, the listener cannot feel anything.” Multi-instrumentalist Douglas Ewart, friend and collaborator of Smith for over 50 years since their days in the Muhal Richard Abrams Orchestra, describes the process of creation as similar to cooking. To paraphrase: we have the ingredients which come from our lives, our experiences, our understanding of the music in many varied settings. In the live creation, a delicious stew is concocted, not by random happenstance, but through disciplined choices.

Read More

Smith explains the title track thusly: “Shimmering Light is light that comes in multiple particles that flow as a beam and because it has multiple particles it shimmers.” So too with sound and music, which Smith believes has a physical manifestation as particles. This vibration triggers a physical as well as an intellectual emotional feeling in the listener or responder in some way through the artist’s inspiration.

The CD opens with the nearly 16-minute “Constellations and Conjunctional Spaces”, which seems to start mid-phrase with Ewart on bassoon and Smith on English horn. We are treated both to soaring notes and those plumbing the depths, both instruments cutting through the silence together and in conversation with drums. The title track comes next, opening with a sonic chime, greeted by extended muted trumpet. There are shimmering shaker sounds undulating beneath, hints of talking drums. We could be on a journey through a forest with the lights glinting on the leaves with Miles Davis as our guide. Ewart joins on flute, a gentle presence in contrast to Smith’s bolder tones. This is not background music, nor does it incite. It is a pleasure dome for the senses. Truly magical.

“Super Moon Rising” opens with mbira and drums rolling back and forth, trumpet repeating a march-like ditty. The drums continue to roll, turning to staccato fire. Ewart contributes percussion from one of his many, often self-made instruments. “Unknown Forces” alludes to the East in tonality and is more meditative in places. Final track “Dark Tango” is short by comparison and arouses the audience’s rapturous applause. Astral Spirits has done a superb job with the design of the album: the photographs of the group in performance in a purple haze provide a great entry to the sound, as does the enigmatic cover art. This is a constellation not to be missed.

For more information, visit Astral Spirits.

Read in The NYC Jazz Record

Organic Music Theatre Chateauvallon 1972

Don Cherry’s New Researches (featuring Nana Vasconcelos) (Blank Forms)

The NYC Jazz Record, November 2021

Don Cherry, who would have turned 85 this month, and his wife and collaborator, Moki, left New York behind in 1970 to establish a home of music and art in Tågarp, Sweden. This 1972 concert, whose audio was taken from a video of the titular French festival, represents Cherry’s departure from the exploitative world of jazz, drugs and city life and his immersion in music as an environmental alternative way of life.

Read More

Opening track “Dha Dhin Na, Dha Tin Na” is an Indian chant, the audience heard clapping a rhythm with a cowbell and Cherry on piano and vocals accompanied by saxophonist Doudou Gouirand. The music flows into a charming second piece, “My Butterfly Friend”, Cherry singing the title phrase repeatedly. Nothing of the avant garde that made him famous is to be found here except, perhaps, the improvisations and way the pieces flow into one another. On “Ganesh”, Cherry sings with piano, barely accompanied by Gouirand and Naná Vasconcelos on light percussion, creating a feeling of folksy mysticism. Hari Krishna is invoked and Cherry sings to the audience, “I wanna give you something from my heart.” He jokes that folk don’t smile much in the North as compared to folks from the South. It is a happy, playful scene that is set, like being immersed in a hippie commune in the ‘70s.

At least two decades before it became a household word, what is here is world music, taken from many spheres and melded into a sound that speaks to Cherry’s concern that music be a part of everyday life with no separation between performers and audience. There is Brazilian, Malian, South African, Indian and Native American music in these tracks. “Relativity Suite, Part 1” features the donso ngoni, a hunter’s guitar from Mali, which brought Swedish reedplayer Christer Bothén to Cherry’s attention when Cherry saw him play the instrument on TV, and Vasconcelos on berimbau, an instrument of African origin played in Brazil.

The two-CD set is attractively packaged, with a bright orange cover image reminiscent of Moki Cherry’s paintings. The liner notes consist of an essay written by Magnus Nygren, Cherry’s biographer, with Andrew Lampert pointing to two fundamental concepts created by Moki and Don. The first is “Organic Music Theatre”, described in the book The Organic Music Societies, also published by Blank Forms, as “a collaborative intermedia initiative” that emerged from the Cherry’s home in rural Sweden, “open space for musicians and community members to produce art and music in their home.” The second is an improvisational technique called “collage music”, which builds the performance through the use of smaller composed pieces and music created on the spot. The notes also contain black and white photographs of Don, Moki and the Organic Music Theatre in different settings and the scenography that Moki created, consisting of banners, carpets and costumes, an essential part of the musical process of Organic Music Theatre.

This project does a great job of preserving a critical part of the work of Don and Moki Cherry and their life contribution to expanding jazz, music of the spirit.

For more information, visit blankforms.org.

Read in The NYC Jazz Record

A Fireside Chat with Lucifer

Sun Ra & His Arkestra (Modern Harmonic)

The NYC Jazz Record, October 2021

This reissued album’s new liner notes by Sun Ra estate administrator Irwin Chusid provide insight into the story of the recording, which adds a nuttier flavor to the music: the ongoing use of the Variety Recording Studios in Manhattan after the band moved to Philadelphia; the anecdote John Szwed tells in his book that Sun Ra had asked fledgling members of the band to call him “Lucifer”; and the fact that the words motherfucker and ass were not part of Sun Ra’s daily vocabulary on or off stage. As the recently departed Phil Schaap made plain, the stories of the making of the music are just as important as the music itself.

Read More

The opening track is “Nuclear War”, Sun Ra at his most playful. The call-and-response vibe, Sun Ra’s characteristic chords and a danceable rhythm all make the heavy message easier to swallow whole. The fact that it is a studio recording accounts for the clarity of voices as Tyrone Hill and June Tyson sing with Sun Ra as if right in your living room:

“Nuclear War (yeah)

They talkin’ ‘bout (They talkin’ ‘bout, yeah)

Nuclear War (yeah)

It’s a mother fucker, don’t you know

(If they push that button, your ass got to go)

What you gonna do without your ass?”

What indeed? Perhaps reflect as Sun Ra does on the next track, “Retrospect”, where sonic tones in contrast to somber horns seem to be seeking a solar frequency. From those high plains, we swing into “Makeup”, a composition that could be a standard played at the Vanguard tonight.

The B Side is the title track, filled with soothing and frenetic solos over strobing, pulsing rhythms. There are no voices save the instruments (alto saxophonist/flutist Marshall Allen, tenor saxophonist John Gilmore, baritone saxophonist/flutist Danny Ray Thompson, trumpeter Walter Miller, French horn player Vincent Chancey, trombonist Hill, bassoonist/percussionist James Jacson, bassists Hayes Burnett and John Ore, drummer Samarai Celestial and percussionist Atakatune). Towards the end, Sun Ra has a quiet conversation with the devil on keyboards. Stuart Baker writes in the iconic Freedom Rhythm and Sound: “Sun Ra felt the recordings were messages for a future time when people would better understand the music he was creating ...They were also created for the ‘private library of God’ and dedicated to the creator.” That future time is now.

For more information, visit sunramusic.bandcamp.com. Sun Ra Arkestra is at BRIC House Ballroom Oct. 22nd as part of BRIC Jazzfest. See Calendar

Read in The NYC Jazz Record

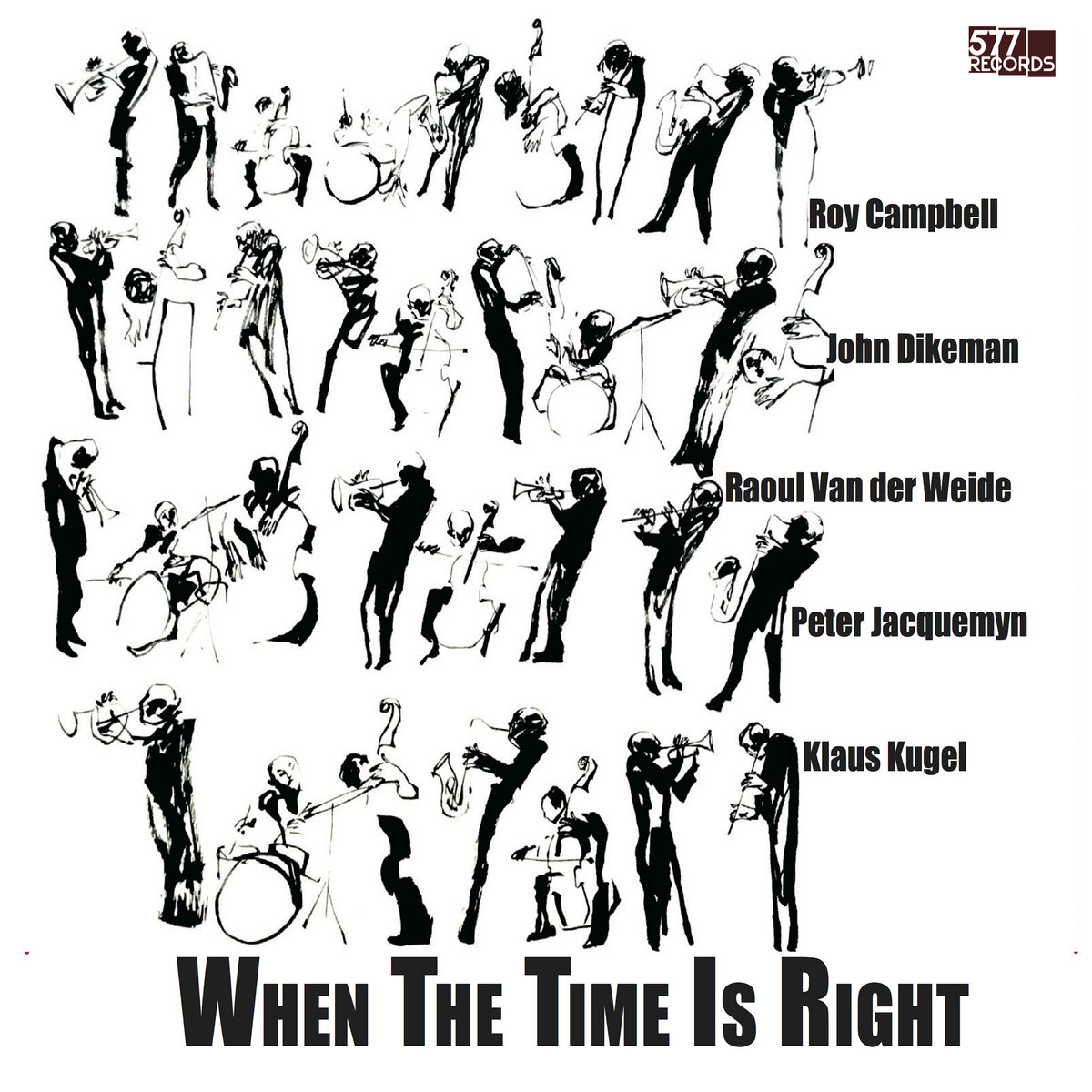

When The Time Is Right

Roy Campbell, John Dikeman, Raoul van der Weide, Peter Jacquemyn, Klaus Kugel (577 Records)

The NYC Jazz Record, September 2021

This CD appears at a moment in New York when an exhibition and book exploring the life and work of Don and Moki Cherry, Organic Music Societies, recently closed and the BBC aired a 2011 program entitled Blue Notes, Cold Nights discussing Cherry and other Black musicians’ relationship to Europe and also Scandinavia in particular. The critical element of these relationships was the desire of Black musicians to live and play freely, outside as much as possible, of the daily vortex of U.S. racism and the music business. This recording is a legacy of those roots.

Read More

Trumpeter Roy Campbell (who would have turned 69 this month; he died in 2014) was a disciple of Cherry and others in the collective avant garde jazz movement. He lived in the Netherlands in the ‘90s and this music, a single 37:46 piece recorded at the Bimhuis in Amsterdam as part of Doek 2013 Festival, springs from that space. Of his collaboration with Campbell, though they played together a total of six times and only once in this ensemble, saxophonist John Dikeman recalls, “Roy was a truly authentic voice. He also had the amazing ability to play in very different situations of completely different dynamics or aesthetics. He did so effortlessly and somehow managed to fit completely in every environment and still sound exactly like himself.”

Both share an interest in folk music and Egyptology, a reference to which could be gleaned from the almost hieroglyphic forms of musicians in black and white adorning the cover. Peter Jacquemyn, who is both the bassist on the recording and a sculptor, contributed these drawings. His experiments with the voice sound like a didgeridoo at points. This limited 500-CD edition is straight and to the point: a black and white photo of Campbell playing his horn confronts one when the CD is lifted from the sleeve; there are no notes, but the introduction to the CD on the label’s website includes this quote: After their improvisation, Campbell told his fellow musicians, “what I liked the most is that from the very beginning, we went directly to the point.”

The set opens with a single note from Dikeman, which is quickly engulfed in a rain of sound, trumpet wailing as if addressing a different crowd and a fiery rhythm section completed by drummer Klaus Kugel driving the group forward with breathless energy.

In contrast, there are lyrical, meditative interludes in which Campbell plays on muted trumpet, flugelhorn and flute something akin to folk melody, softer, gentler yet still with such an unfamiliar tonality. The picture thus painted is ethereal, creating and providing a futuristic space reminiscent of Sun Ra. Raoul Van der Wiede uses his cello as a percussive instrument. Perhaps this is the point of the experiment, to allow one the space to place in it or on it whatever springs to the imagination. If the enthusiastic applause and excitement of the presenter at the end of the set are anything to go by, the time was definitely right!

For more information, visit 577records.bandcamp.com. Dikeman is at Dizzy’s Club Sep. 23rd-24th with William Parker. See Calendar

Read in The NYC Jazz Record

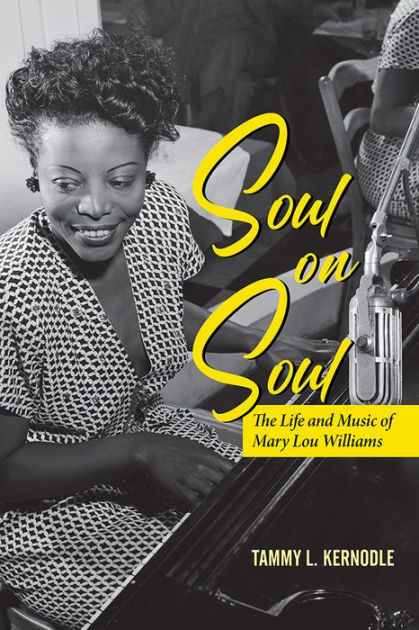

Soul on Soul: The Life and Music of Mary Lou Williams

Tammy K. Kernodle (University of Illinois Press)

The NYC Jazz Record, June 2021

16 years after it was published, this revised edition, a holistic view of the “life and music” of Mary Lou Williams, who died 40 years ago, will perhaps find a different and more discerning audience, arriving as it does on the heels of the “#MeToo” movement and a feminist insistence on being heard, recognized and believed. Tammy K. Kernodle couches her exploration in a spiritual space, her experience of Mary Lou’s Mass, what she calls “worship music with a progressive social consciousness”, bringing her to explore Williams’ work at the “intersection of her faith and her love of jazz music.”

Read More

The first chapter sets the scene: Jim Crow south with a mother who played the pump organ and sang in church; a father who abandoned them; and a stepfather and grandfather who encouraged her amazing ability to play what she heard by ear. A life of poverty was to haunt Williams for most of her life, but it was also one rich with family and music.

In 1915, her family moved to Pittsburgh where she began formal education in music. She progressed to playing in Union bands, soaking up the atmosphere at rent parties and clubs her stepfather would sneak her into to play. Kernodle is careful to describe the way in which male support from her family gave her a level of self-esteem, allowing her to play confidently as an instrumentalist and stay away from the feminine roles so many other Black women musicians were forced to play. It is said that throughout her life she did not smile during performances and made little attempt to engage with her audience. Williams traveled on her own at an early age on the Theatre Owners Booking Association circuit, the breadwinner for her family.

In addition to the strength as a player, Williams was sought after as a composer and arranger. The book discusses comparisons with other female musicians of the time, Hazel Scott in particular, who was seemingly a far more activist figure. Williams’ love life and marriages are intertwined with the story of her music. Of her marriages to John Williams and trumpeter Harold “Shorty” Baker, she said “[I] didn’t marry men, I married horns. After about two weeks of marriage, I was ready to get up and write some music.” She traveled extensively in Europe but also faced many periods with little money and without steady companionship. The latter part of the book deals with her spiritual conversion; work to help drug addicts, for whom she established the Bel Canto Foundation; and, in the last year of her life, The Mary Lou Williams Foundation, providing music scholarships for gifted children.

The preface to this edition tracks Williams’ legacy from Geri Allen’s leadership of the Mary Lou Williams Collective to Dr. Billy Taylor’s founding of the Mary Lou Williams Women in Jazz Festival at the Kennedy Center. The book contains a short discography as well as a photo section, showing a stunningly attractive woman as she ages.

For more information, visit press.uillinois.edu

Read in The NYC Jazz Record

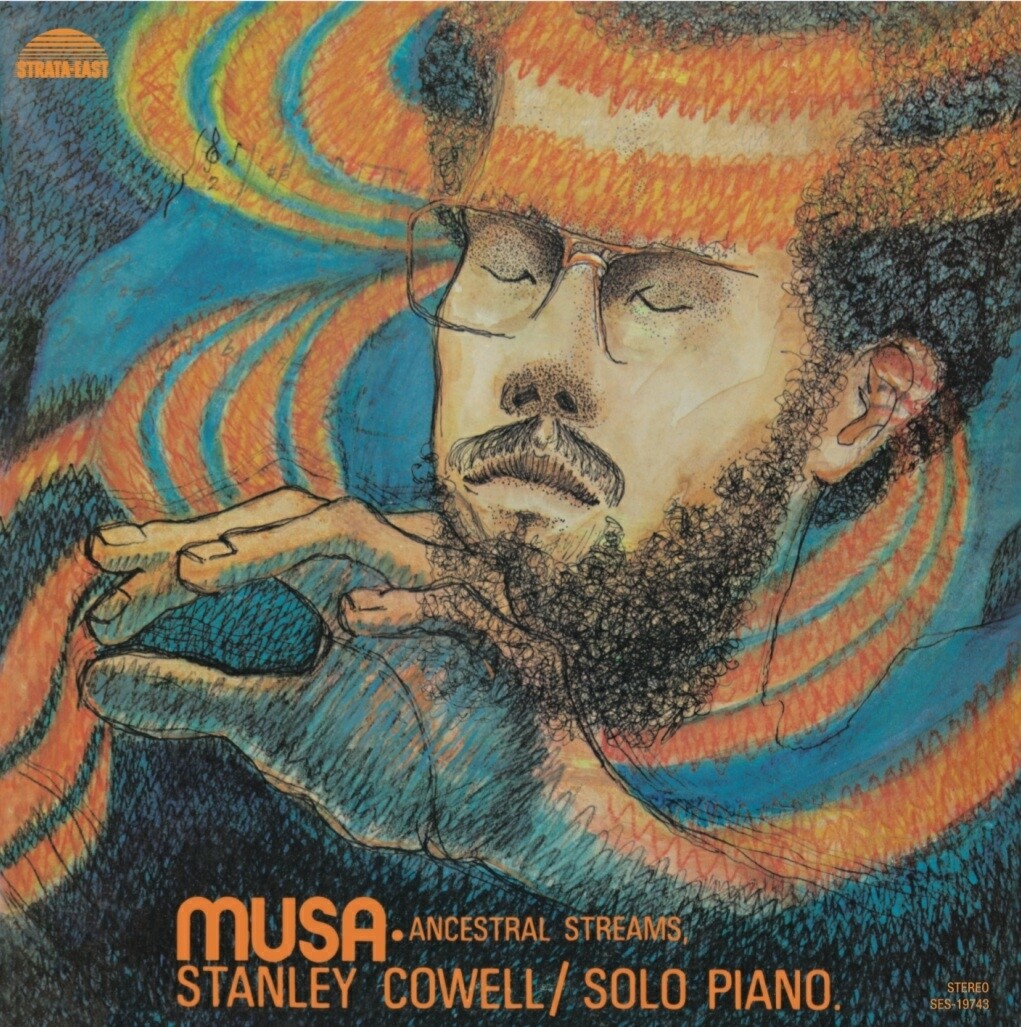

Musa - Ancestral Streams

Stanley Cowell (Strata-East - Pure Pleasure)

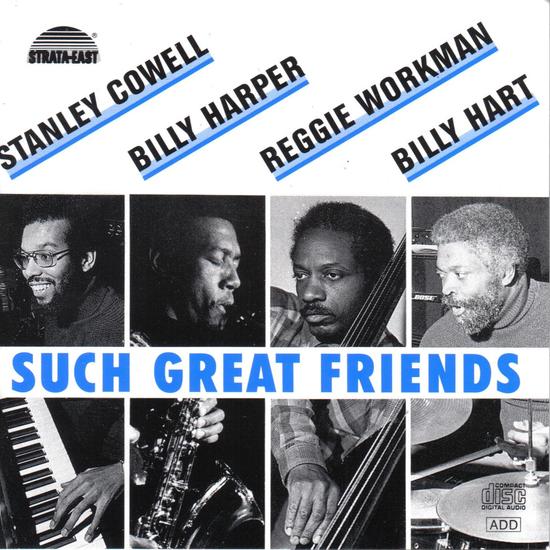

Such Great Friends

Stanley Cowell, Billy Harper, Reggie Workman, Billy Hart (Strata-East - Pure Pleasure)

The NYC Jazz Record, May 2021

Stanley Cowell could be described as an unsung hero in the sense that while he was revered in the music community, he did not have nor did he seek the fame of his contemporaries. Though he won many awards and accolades during his lifetime, he was really a musician’s musician judging by the caliber of leaders like Rahsaan Roland Kirk, Max Roach, Bobby Hutcherson, Marion Brown and Harold Land who drew upon his services. The thing that his wife Sylvia Cowell drew to this reviewer’s attention on his passing last December was his role as a father and a husband. Cowell, as attested to by his daughter Sunny, took each of his roles seriously and found a way to balance a deep commitment to exploring his chosen musical instrument with an equal commitment to his family, his teaching and to social justice. Listening to and researching this pair of remastered LPs, this reviewer was struck by the quality of Cowell’s relationships with his family, his fellow musicians and his students.

Read More

Musa - Ancestral Streams was his first solo piano album. The word Musa means “saved from the water” in Arabic and other languages. The album is perhaps conceived as an homage to the history of the music from which it is drawn. Released by his own record company Strata-East in 1974, this gorgeous album is dedicated to his father, Stanley R Cowell, Sr.: “His encouragement and the opportunities he provided for my musical/spiritual growth I shall always remember.”

Those opportunities included the chance to meet and play for Art Tatum when he was six at the motel that his father owned. Cowell was born in Toledo, Ohio 80 years ago this month on May 5th. It was a rare thing in those days to have a Black-owned business. Many musicians frequented the motel because of segregation, allowing the younger Cowell to see the musicians and their lifestyle. Trained as a classical pianist by day at the University of Michigan, Cowell spent his nights playing jazz in the clubs. As soon as he was done with his studies, Cowell set off for New York, hoping to play with his idols.

It was a relationship that trumpeter Charles Tolliver described as “an instant bond like no other”, a friendship of 53 years that began at a rehearsal for a new Max Roach Quintet. That friendship spawned the independent label Strata-East, which Cowell described in an interview as a condominium: “Charles and I created the corporation—in other words, we owned the building. The artist-producers owned their recording(s)—in other words, they owned space in the building. A legal contract agreement was mutually executed by SER and the artist-producers.”

Cowell drew on the business acumen of his parents and the seminal idea for those times of owning what one had created. A Jazz Messenger blog post noted, “From the outset, presentation and quality became a central part of the creative vision. The label’s sharp black and white logo by graphic designer Ted Plair set the tone. Always pressed on the finest vinyl, Strata-East’s recordings were pressed in limited numbers, adding to their cultish status.”

Pure Pleasure has remastered this album perfectly and faithfully reproduced the album sleeve featuring the artwork of Carol Byard, who depicts Cowell emitting spheres of orange, turquoise, blue and purple in a trance-like state, fingers outstretched. The inside of the gatefold shows a spirit transcending in a black and white painting of ancestral symbols. Magical.

This reviewer saw Cowell and his daughter perform the song “Equipoise” at his last live recording at the Keystone Korner in Baltimore in 2020. The second track on Musa - Ancestral Streams, it is arguably Cowell’s most admired composition, one he returned to many times and which has also been covered by many musicians and sampled by hip-hop artists like The Pharcyde. (See “Equipoise: A Critical Analysis of Covers”, January 17th, 2014 by Ben Gray at nextbop.com/blog). The melody on this solo piano version is haunting, plaintive, yet hopeful. Cowell’s intonation hits that sweet spot, drawing in the listener. It feels like floating on some celestial plane.

Opening “Abscretions” has a definite masculine tone, with the melody placed stridently in the bass clef. It could be a victory march or a Black man striding towards freedom. Coming of age in the ‘70s, Cowell was influenced by the struggles against the social injustices of the time. “Prayer For Peace”, in contradiction to its title, seems to convey more of the turmoil of war than the tranquility of peace, strangely jarring with a rhythmic insistence on change. The final composition on the A-Side is unnervingly short at 2.45. Entitled “Emil Danenberg”, from The Illusion Suite, it is the oldest composition on this side and far more abstract than any of the other pieces.

The B-Side opens with another song from The Illusion Suite, “Maimoun”. “Travelin’ Man” has been described as Cowell’s anthem; he duets with himself on electric piano and mbira (thumb piano). It is a light, breezy tune. “Departures 1” is a frenetic display of virtuosity and brilliant use of every inch of the keyboard threaded with complex rhythms and scales. Cowell ends on the lush ballad “Sweet Song”.

Pianist Jason Moran says of the album: “The record is close to my heart. This is the solo piano record that showed an expansive relationship to the jazz piano canon and at the same time, upended the notion of how the canon sounds. Many times Cowell sounds like ten hands instead of 10 fingers. In essence, he is a structuralist, but one that can see and okay the negative and positive of the sound. His strategies evolved the piano. Lastly, this recording is important to hip-hop producers and Stanley's sounds found a new garden to sprout from for a new generation.”

Such Great Friends speaks again to relationships, this time with fellow musicians. The album cover is crisp black and white with blue accents and the title in a deeper blue. The face of each musician—Cowell, tenor saxophonist Billy Harper, bassist Reggie Workman and drummer Billy Hart—is shown with a separate picture of their hands on their instruments below. The back cover features the band whole again (photos by veteran Ray Ross, who died in 2004). Each participant (notably, for that time, each with his own publishing company) brings a composition. Three songs exceed 10 minutes except Hart's “Layla Joy”; Workman's “East Harlem Nostalgia” clocks in an impressive 16:58.

Cowell's contribution is “Sweet Song” from Musa - Ancestral Streams, opening with solo piano until Harper glides in. The pace is slow and measured and drums light and spare. Harper's “Destiny is Yours” has a cute melody and traditional head-solos-head form. “Layla Joy” features a short drum solo but is dominated by tenor. To close, “East Harlem Nostalgia” opens with several minutes of solo bass before the band takes us for a ride through the titular neighborhood, the hoots and hollers of Harlem streets echoing in Harper's horn.

These two reissues are excellent additions to Cowell's legacy, hopefully bringing the music to new fans. He was a practicing Buddhist and Bodhisattva of the earth and his music and spirit will live on.

For more information, visit purepleasurerecords.com

Read in The NYC Jazz Record

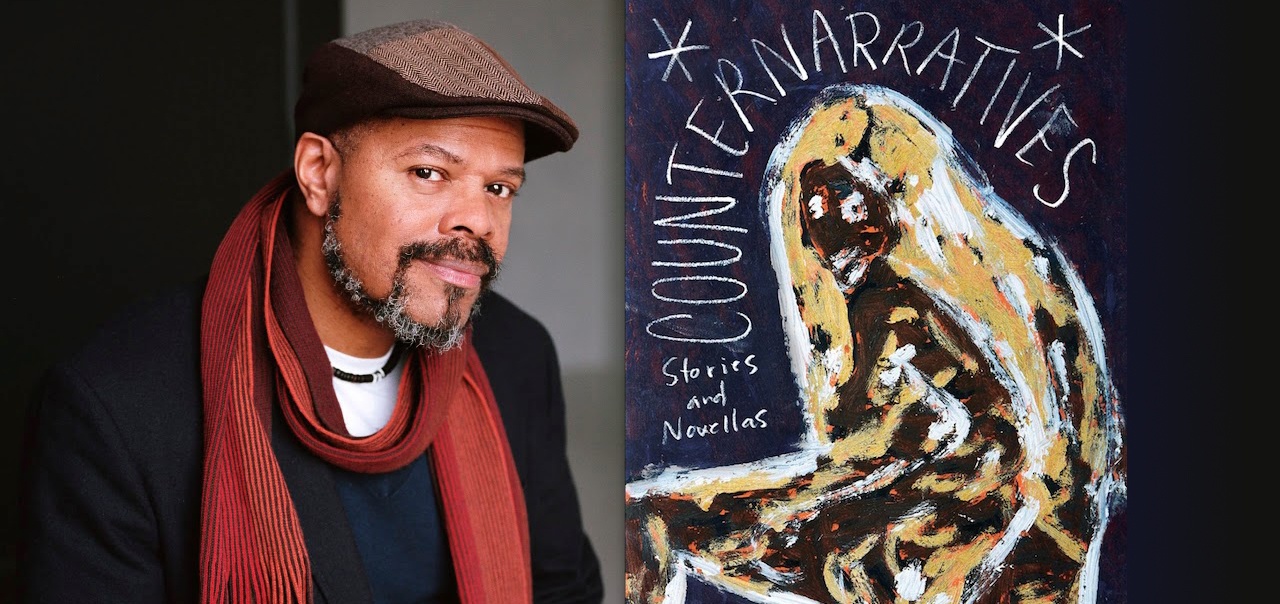

An Interview with John Keene on the Power of Narrative From 1613 to Today

The Brooklyn Review, Spring 2021

John Keene is a Distinguished Professor of English and African-American and African Studies at Rutgers-Newark, where he has served as the chair of the African-American and African Studies department since 2015. In his own words, he says, “I'm a writer, a translator, an artist, an editor, and a mentor.” He is affiliated with organizations including Cave Canem, where he has served as a fellow, and the Dark Room Writers Collective, which he joined several years after obtaining his undergraduate degree at Harvard University. He is currently a board member of the African Poetry Book Fund, which aims to make available works by poets from the African continent and was founded by Kwame Dawes and is based at the University of Nebraska. He is also a recipient of the MacArthur Foundation Fellowship, which he was awarded in 2018.

Widely celebrated as an experimental writer, John has published two collaborative volumes of poetry, including Seismosis (2006) and GRIND (2016), a chapbook of poems called Playland (2016), and translated the Brazilian author Hilda Hilst's novel Letters from a Seducer from Portuguese. His first novel Annotations was published in 1995, and his short story and novella collection Counternarratives (2015) was lauded to wide acclaim.

"I'm a writer, a translator, an artist, an editor, and a mentor."

Monique Ngozi Nri: I'm curious what your take is on the Amanda Gorman poem that she read at the inauguration on January 20.

John Keene: I want to begin by saying that I honor her as a young poet. I encourage people to read poetry. I encourage people to write poetry, and above all, to listen to poetry and sit with poems. I think what was very clear to me is that her poem comes out of several different traditions and that these are probably not the traditions that are being regularly taught in colleges and universities.

Read More

John Keene: On the one hand, we just had a fascist insurrection. We have state murders of Black people. We have the continued dispossession of indigenous people. I understand the criticism that some people may have that delivering a poem on behalf of any administration that is going to pursue empire is problematic—whatever the political party.

On the other hand, I do think the new administration is going to be better in some key ways than the former administration, which had to be dragged out kicking and screaming, and I do celebrate this young poet. She is quite talented.

MNN: Looking at the second and third stories in Counternarratives and your description of the dynasties of enslavement and slave owners, I think it's an ironic twist that you put on some of the statements that you make about how these people think about themselves in relation to what they're doing to people of African descent. I was struck by the first story. It reminded me of The Kingdom of This World in the sense that it was an in-depth look at the life or the experience of this particular man.

I wondered why you chose to place that story at the beginning of the book, and if you could talk a little bit about the idea of making that story, our story, available and present for people to encounter.

JK: I would say that with “Mannahatta,” I was very interested in thinking about a counter-history in terms of the United States' origins. That's not to suggest that “Mannahatta” stands as a kind of founding statement; the U.S.'s founding by its very nature is problematic. I wanted to think through and write the story of someone who arrived very early, who was not indigenous, who was a mixed-race person from the new world but also a product of the old world, whose goal was not to be a settler colonialist or an extractive colonialist. Juan Rodríguez (Jan Rodrigues) was a real historical figure. When he arrives in what becomes Manhattan, what becomes New York City, he is engaging in trade, but his idea is not “I'm going to lay claim to this world” but rather, “I want to become a part of it.”

He wants to separate himself from the Dutch colonialists on whose ship he's working. I was fascinated by this idea of a figure whose originary presence is right in front of us and, at the same time, remains so obscure. Several organizations and one of the departments at CUNY have honored him; they created a plaque for him, and they had a full ceremony for Rodríguez. But he remains utterly obscure, even to New Yorkers.

It's fascinating in the sense that he was apparently born in Santo Domingo, and New York has one of the largest populations of Dominican-Americans and, as a city, has one of the most sizable populations of Latinx people in the U.S. Among U.S. cities, New York has had and still has the largest numerical population of people of African descent in the entire United States. One would think that there would be, even if not regular celebration, at least more discussion of someone like Juan Rodríguez.

His story challenges the narrative that we have been handed down about the origins of this country—and what might have been and what became possible. I think it's very important that, so early on, this Black figure, this mixed-race, non-English-speaking figure, was there at the beginning. This was around 1613—a few years before when “The 1619 Project” commences. I say this not to erase “The 1619 Project,” but to underscore that histories are complex.

Of course, we know there were people of African descent who arrived with the Spaniards, etc. It was very important for me to use that as a thematic and metonymic starting point for the collection because it both grounds us in this idea of what U.S. American history is and opens up spaces of possibility for thinking in broader hemispheric and global terms.

Peter Soucy: The title of “Mannahatta” shares its title with Walt Whitman's poem “Mannahatta.” We recently spent a semester learning about Walt Whitman, him being racist, and his view of America totally overshadowing Black and indigenous people's history: a view of a united America but only for white people. How much do you see your story as an inverse of this narrative?

JK: That was certainly in my thinking. On the one hand, Whitman is really one of the greatest and most influential American poets—not just for American literature but also for literature all over the globe. His influence extends in all directions. On the other hand, you're right. Whitman, like most White people of his generation and preceding and subsequent generations, could be extremely racist. He had a pretty hypocritical idea about a kind of brotherhood of White people which, interestingly enough, you see animating the pre-Civil War period: this clash between the Union and Confederacy, and then afterward. As the country is reuniting, one understanding is that what is really being reunited is whiteness and white social capital and power. Power in exchange for throwing Black people under the bus and stripping away their rights. Northern capital can do what it wants to do. This is a kind of recurrent theme.

To go back to Monique's question, one of the things I did not mention but relates directly to this idea of the uniting of whiteness is this question of capital—in all its forms: social, political, economic, cultural, etc. What does it mean that the Dutch viewed Manhattan or Mannahatta primarily as a trading post? I wanted to try to think through another way into our past, our understanding of capitalism—to think about how this character views what he's doing in terms of trading and engaging in commerce of various kinds with the indigenous people.

In a sense, the title is both an ironic criticism of Whitman and also an invocation of him. One of the things that happens in that story, as we see so often in Whitman, is his really remarkable invocation of the rivers surrounding New York. You think about “Crossing Brooklyn Ferry,” Whitman's famous poem. I tried to make sure that one of the first things that Juan Rodríguez sees is the East River, but he also sees Long Island, which includes Brooklyn. That's what he views on the other side of that shimmering river as he sees this other world of freedom. He's part of this new world, this other world. He can see its expansiveness, but his desire is not to own it, to dominate it, but to walk through that window into another life in which he might live harmoniously with this new world and become part of it.

Elizabeth Hickson: You mention the idea of this new world that is an “other world,” and I started thinking of conceptions of translation—of strangeness, a thing and its other. How does your translation work relate to that idea, and how does translation theory influence your writing in general?

JK: One of the things that I'm thinking about is Édouard Glissant's idea of relation and opacity. Related to that is the question: What does it mean to live with and not to dominate? What does it mean to be together without being the same—to fully accept the idea of difference and all its difficulty and pain and complexity, and to be in a continuous conversation about that? When I think about translation, that is one of the things that has profoundly influenced my work.

"I find that, whenever I translate or read translations, it transforms my sense of what's possible in a good way."

MNN: I was struck that part of your work with Kwame Dawes and the African Poetry Book Fund involves bringing actual African poets into print or reprinting their work. I feel that that is an area that, even for myself, is relatively unexplored, and I'm Nigerian/Barbadian. Can you talk a little bit about the importance of those translations, and the importance of that work for our understanding as a whole?

JK: One thing that becomes clear when you look at the work of poets who have not been so appreciated, whose work has been reissued as selected poems or collected poems, and work that has not really been in English or even in a European language is that it changes your understanding of history, of literary history, of aesthetics.

I find that, whenever I translate or read translations, it transforms my sense of what's possible in a good way. I think there's a way in which it brings a centrifugal quality to the conversation, particularly in mainstream American “elite” circles about literature.

MNN: If you take “On Brazil,” in this passage where Londônia is about to testify, the way that this voice describes the scene reminds me very much of what we're going through now with the trial of Trump, and this kind of split perception as to what is going on:

“Despite the seriousness of the affair, a current of easy familiarity passed among the men. Several laughed at Londônia's account of the circular march through the jungle.”

What is your intention with speaking with that voice? Because at some points, I just laughed out loud.

JK: I would say: I want you to laugh. There are actually several places throughout Counternarratives where some of my intention was to be funny, but in a very wry, ironic way. In that passage that you cite, my goal was to lay bare how power works. You have the indigenous people who were the targets of this marauding party from the empire. And you also have this African Quilombo, where people escaped chattel slavery.

Both the story's protagonist the Colonel himself—and the people around him—and the person arguing from the other side who is opposing him are still part of power. They're just different annexes of power; they're up against each other, but depending on where you sit in the hierarchy, as is the case with the Londônias-Figueiras family, the Colonel has so much more power. It does not matter how beautiful the arguments on the other side are. This is how power works.

He knows he's not going to be punished harshly for genocide: the outright killing and slaughtering of people. Of course, this is justified under the ideology, the ethos, the morality, the ethical structure, and the society in which he lives. They have created a space or place for this: to seize land, to seize power, to kill people. I wanted to think about: Usually, if you're a historian, when a voice or voices are recounting things, there's a way that you're going to do this. Your own perspective is going to enter, but with great care. Your prose is going to be shaped by the way that you think about the archive you're exploring and whose materials you're working through.

I wanted to be much more overt in this story: to bring in a range of discourses, an array of voices, that keep disrupting or destabilizing any easy understanding of how to see or read or think about what's going on.

MNN: It's also fascinating to me that at no point in the story, “An Outtake” is it discussed that the story's protagonist Zion is the so-called master's child. What are the pieces that you're putting in the narrative to break up assumptions about what stories should look like or have looked like?

JK: You're one of the rare people who has noted that Zion was thought to be the son of Mr. Wantone. That goes right over people's heads. We know about Zion's mother. In a sense, we know about his surrogate mothers and the people around him: his family, the constructed family. We hear very little about his father. This was one of the first stories in Counternarratives that I wrote. I was fascinated by this idea of what the German literature scholar Andres Huyssen calls “analytical fiction.”

Huyssen, when speaking about the German writer Alexander Kluge, raised questions about how you engage the reader critically yet so that they keep reading to the end. You include these critical aspects that defamiliarize. How do you zoom in? How do you zoom out? I don't mean just in a technical sense, but I mean in terms of critique.

I was particularly fascinated with this idea of slavery and the American Revolution. When I think about most discussions of the American Revolution, even today, slavery is there but [not really]. I think about the popularity of Hamilton. As my colleague Lyra Monteiro at Rutgers-Newark and other people have pointed out: If Hamilton really looked at that moment in time and Alexander Hamilton himself, etc., we'd probably have a very different musical. Other people would have come to the fore. It's fascinating.

Of those main figures, the one who was not a slave owner and was no fan of slavery was John Adams. He's basically not part of Hamilton. That's not to criticize Lin-Manuel Miranda, but to say with regard to the character Zion, slavery, and Massachusetts: What does it mean to think about the place of someone so radically unfree at the very moment when and in one of the very places where the rhetoric of freedom is so powerful. The thing about Zion is: He's not a noble character, but he is an emblem of radical freedom. He does not feel that any rule of law, and especially the dominating structure—that brutal, oppressive, dominant structure of chattel slavery—should constrain him. However, there is no space or place for someone like him at all in this world.

"I wanted to be much more overt in this story: to bring in a range of discourses, an array of voices, that keep disrupting or destabilizing any easy understanding of how to see or read or think about what's going on."

EH: I wonder if this concept of radical freedom is something you're actively thinking about as you write. Is genre something you're thinking about, or do you apply this idea of radical freedom toward the very idea of writing itself?

JK: I've been writing poetry and fiction, poetry especially, going back to childhood. I wrote fiction and poetry when I was in high school and college as well. I think I'm very aware of the traditions that I'm writing out of, though, I try as much as possible not to censor myself when I'm writing. Now that I'm older, I have a clearer sense, when I start writing, of what it is I'm doing.

With the exception of one book I published a few years ago with Nicholas Muellner (GRIND), which is a wonderful collaboration, every other book that I've published I've encountered some challenges getting them published. I think it's very important as a writer—and I say this especially to student writers, apprentice writers, emerging writers—to be as open and free as you possibly can when you're writing.

PS: Do you think you would be able to create the same kind of points or get across what you're trying to say if you weren't allowed to fictionalize, or is that balance between fiction and nonfiction important?

JK: I think about so many writers like Kiese Laymon, Eula Biss, etc., who have taken really fascinating and provocative routes with nonfiction. However, I'm personally interested in the possibilities of fiction as a genre.

Well before autofiction became a hot genre in the 2000s, I

published Annotations. There are so many different works

that inspired it. Clearly the very obvious ones: works by Lyn

Hejinian, Ntozake Shange, Samuel Delaney, Clarence Major, and other

people I mention in the book itself, as well as people I didn't

mention, like Kathy Acker who I was reading at the time. Annotations

comes almost 20 years after Serge Doubrovsky coined the term

“autofiction,” but I still think there are so many interesting

things one might do with that line between fiction and nonfiction,

particularly on the fiction side.

A few years ago, I taught

Anelise Chen's So Many Olympic Exertions. I also taught

Sheila Heti's How Should a Person Be? and Chris

Kraus's

Aliens and Anorexia, among others. Each could be viewed as

nonfiction, as memoirs, but each also functions as a novel. When I

read Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s novel Americanah, I

thought it was so fascinating to see an aspect of the world that I

inhabit portrayed as fiction. Of course, her perspective is

different than my perspective; she’s Nigerian-American, and

I’m African-American. But in so many ways, there were these

powerful moments of recognition.

I am trying to consciously think, “What does fiction do? Why do we write fiction? Why do I write fiction? What are fiction's possibilities, particularly now?” I think about the extraordinary power of narratives. If nothing else, the QAnon conspiracy should make anyone who is working with narratives raise the question of: “What is it about particular narratives that make them so compelling, so galvanizing, so mesmerizing that they become the means to explain anything and everything?”

They can be extremely dangerous. I hope that we think more about narrative and its power because it is extraordinarily powerful when it comes to human beings and the ways we understand the world. We live in narrative. We construct narratives. We are the products of narratives. We organize our lives in and as narratives. The narratives that we create are going to be particularly important now. We see how important narrative is for even just the very idea of what we call democracy or society or our ability to live on a globe that is increasingly endangered. Everything is shaped by narrative.

MNN: You mentioned the Dark Room Collective and Cave Canem in terms of being a fellow. What place does community play in your existence as a writer?

JK: I teach at a university, so I have an amazing community of colleagues who are writers and scholars, students, staff, and people I work with. It's very invigorating. They keep me thinking and dreaming. I also think about the larger community of writers and different communities of writers that I'm part of.

When I was starting out, the Dark Room was particularly important because it was a group of primarily young Black writers, as well as artists, musicians, and filmmakers, who were not part of an established institution. We had to create our own thing, if not an institution, then our own space for the kind of work we wanted to see, the kind of writers we wanted to learn from, and the kind of community we wanted to bring into the world.

Of course, I also think about the old OutWrite conferences, which were an invaluable space where LGBTQ+ writers came together when the AIDS pandemic first hit. I think of Fire & Ink and how it has brought together Black LGBTQ+ writers.

I think communities are very important, especially for writers. When you're working independently for so much of your time, having a community or communities that you can share your work with, bounce ideas off of, and transform the world with is incredibly important.

EH: I'm wondering if there's anything you're working on now that you'd be willing to share with us.

JK: I'm working on several projects, but I do have a book of poetry, titled Punks, which is scheduled to appear in November from The Song Cave, so I'm working on that. I also have some long-form fiction projects that I've been working on for a while.

There is also a wonderful anthology that Kevin Young just edited: African American Poetry: 250 Years of Struggle and Song. That's a marvelous gathering of work, and I'm very happy to say—thanks, Kevin!—I have some work in there too that's quite formally experimental. That's a volume where you get to see a really extraordinary range—and you see the richness and depth and history.

"All around us, people are dying. So many of them are elderly, so many of them are Black and brown…The question is: How do you make sense of that? How do you write about that?"

MNN: Has your writing been affected by the pandemic at all?

JK: As you all know, being in the New York metro area was terrifying back in March, April, and May of 2020. It was a terrible situation in the city and New Jersey. It's almost unnerving to think that, as bad as things were in New York and New Jersey last spring, it eventually became that way pretty much all over the United States now. Truthfully, the past administration's neglectful, incompetent non-handling, and mismanagement of the COVID-19 pandemic, to me, was just another example of a kind of war on the American people, or sectors of the American people.

I lived through the AIDS pandemic, particularly its early days. At a certain point last year, I felt I was reliving some of that earlier trauma and also experienced PTSD. Once again, it's a situation where people are dying and, this time, there was some discussion of it. In the '80s and the early '90s, it was sort of like we weren't supposed to discuss it. There were stigmas, misinformation, and disinformation attached to HIV/AIDS. I started to feel: It's happening again.

All around us, people are dying. So many of them are elderly, so many of them are Black and brown. We've been told by the person in power, “We're rounding the corner; it's going to disappear; it's not really an issue.” I reached a point where I was thinking, “No, this is maddening. I can't believe I'm living through this again.” And we're still in the midst of it. I have a special feeling for other writers, especially student writers, trying to write now, because you're being expected to turn in work and think and be and dream, in the midst of this terrifying situation. In the richest country on earth that prides itself on being a leader and a model, we have the debacle that we witnessed last year and that we're still in now. The question is: How do you make sense of that? How do you write about that?

MNN: Well, thank you for articulating exactly what I've been feeling for the last year.

JK: You shared insights that people hadn't raised before. I appreciate the questions you asked. Thank you all so very much!

Read in The Brooklyn Review

who is the real ambassador?

continuity and contradiction in the life of a jazzman

Artrage Magazine, 1991, UK

It is 3am, Friday night. Ronnie Scott's, home of most jazz aficionados in London, is emptying to the strains of taped music, which is incomparably bland after the frenetic be-bop and melodic swing of the Sun Ra Omniverse 21st Infinity Arkestra. Ahmed Abdullah, an intermittent trumpeter with the band over the last eighteen years, is engrossed in conversation with a slightly drunk, but earnest young man.

"It was brilliant man, brilliant... but how come no-one knows you're here? I only found out yesterday, man." The questioner is the achetypal stereotype of a British jazz fan-greasy, with lank dark hair and pasty skin- draining a beer can, each sentence is punctuated by "brilliant man."

Abdullah explains the history of the Sun Ra Arkestra and with it, a large chunk of the history of African American jazz. He conveys a love of the music and its practitioners, a deep knowledge and respect for them.

Read More

Describing his own musical apprenticeship and his membership of the legendary Sun Ra band, Abdullah re-creates a jazz world peopled by masters of their craft, masters of the eras of swing, be-bop, avant garde. Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong, Miles Davis, Ornette Coleman, Fletcher Henderson appear in his narrative alongside other musicians like Cal Massey, Freddy Hubbard and Charles Moffet - musicians who live or have lived through their craft.

"The jazz tradition is African-American. It comes through the efforts of a people to have their humanity recognised. For many years it was the only way that people could really show a certain dignity of spirit. Jazzmen were revolutionaries."

There is some evidence of the truth of this statement in the lives of renowned musicians, like Charlie Parker and Miles Davis, both of whom categorically refused to live lives imposed on them by white America. A description of the latter, for example, ran: "he eschews the spotlight, never smiles, makes no announcements... Davis's music is as uncompromising as any in history...winning his success solely on his merits, with no bending to public taste, no conversion to entertainment and absolutely no cultivation of contacts or of anyone likely to do him any good. In other words, no Uncle Tomming."

There 'is little of the uncompromising performance stance in Sun Ra's magnificent presentation. His band is resplendent in glittering robes and head-ties.

At over seventy, Sun Ra has lived through many eras of Jazz. He therefore considers it no sacrilege to mix be-bop, swing and avant garde. His ten- piece band, replete with dancer, entertain both visually and musically. They perform the big band sitting down/standing up routine. They sing in those growly, slightly off key voices which are the privilege of jazz musicians.

Perhaps an attempt at a philosophical stance comes in Sun Ra's self-appointment as a prophet of intergalactic music. In an extract from the cycle Greetings From The Century 20/21st, the refrain "I would have enjoyed myself on this planet. If the people had been alive" is both a comment on humankind's existence on earth and a barb directed at a particularly reserved audience. It is said that Sun Ra is concerned with the imminent destruction of the planet, but this is a different kind of politics from the earlier approach of jazz musicians. which made the very way one lived one’s life challenging to authority. There is little evidence that Sun Ra's message is addressed seriously by critics or audiences.

After a concentrated stint between 1975 and 1978 in which he played every gig with Sun Ra's band, rehearsing and 'hangin' out for ten hours at a stretch, Ahmed Abdullah increasingly took sabbaticals to work with other people and pursue his own musical interests. He currently leads the Solomonic Sextet, an all-star band featuring Charlie Moffet - father of some outstanding musicians and a major attraction since he played with Ornette Coleman on drums. Carlos Ward on alto sax and flute, Billy Bang on violin, Masujaa on guitar, Fred Hopkins on bass and Abdullah himself on trumpet. The music they play has been appropriately described as "a juicy sound ... a mixture of original compositions and arrangements of Brazilian, African and South African songs...”

The authentic feel and fusion of folk songs into jazz forms may result from Abdullah's travels as far afield as FESTAC in Nigeria and Georgia in the USSR. Canto II, a track recorded on the group's last LP, Ahmed Abdullah and the Solomonic Quintet (Silkheart SHLP129) includes a charming Brazilian folk song which draws on what Paul Robeson would have called the pentatonic ear, the musical scale which folk melodies use across the world and through which people "understood and wept and rejoiced with the spirit of the songs." The song was documented by Clementine de Jesus who spent much of her life recording folk songs. The group's repertoire also includes Paul Laurence Dunbar's poem, When Malindy Sings. Those who have heard Maya Angelou's powerful rendition of Dunbar's work can imagine the power of this poetry when combined with the sonorous accompaniment of the cello in a piece called Walk With God. Perhaps in this sense, Abdullah continues a revolutionary Jazz tradition.

He is also concerned about the creation of an audience and the education of future jazz musicians. He cites his own apprenticeship, inspiration through Louis Armstrong on the Ed Sullivan show, growing up in New York's Lower East Side packed with musicians, studying with musicians like Cal Massey, the all important experience of playing on the bandstand with Sun Ra and his own band, as crucial elements of learning to play.

"You have to live through this music or you have to come under the tutorship of a person who's lived through this music in order to play it." Taking jazz to schools, working with and encouraging young musicians, talking to people who are interested in jazz, therefore forms a significant part of Abdullah's activity.

There are, however, contradictions that nag away at the glorious rich nostalgia of then and the barren, harsh presence of now. Jazz has become increasingly severed from African people. It is, as Abdullah admits, the preserve of an elite, in Sun Ra's case, a cult following which is noted for the absence of people of African descent.

Young African-European musicians emerging from Britain - Courtney Pine, the up-coming Julian Joseph, Steve Williamson - while talented and remarkable in their own development are none the less somewhat distanced from the free expression and the 'life' of their African-American predecessors. If this is true for young African musicians. it is starkly true for African women musicians in Europe and the USA.

Abdullah contests the need for the separate labelling of women in jazz' forums. "To me that's the worst kind of pandering there is, because if a person is worth their salt... they don't have to have a separate label… Betty Carter, she can play, Shirley Scott...Jazz is one of the more democratic forms of music that is out there. it really is. If you can play and the cats will accept you or reject you based on that -Can you hang?" Revolution it seems does not extend to breaking down male preserves.

In these times, however, the maintenance of the role of the griot, the preservation and passing on of traditions/cultures culled from past and present experience, is rare. In this sense, Abdullah becomes an articulate representative of jazz, an ambassador for an underground movement, a samizdat, quietly retaining a form of challenging activity for the moment when once again we need songs, rhythm, melody - music that will inspire. The words of Louis Armstrong’s Who’s the Real Ambassador capture this role perfectly.

That I was sent

By government

To take Your place

All I do

Is play the blues

And meet the people

Face to face